The True Myth

CS Lewis famously wrote:

Now the story of Christ is simply a true myth: a myth working on us the same way as the others, but with this tremendous difference that it really happened.

As a Christian mystic, an amateur folklorist and a livelong Lewis fan, I've long agreed with this line of thought. I would go so far as to say (and I believe Lewis would have, too) that all myths are true in a certain sense. Those of us in the folklore and fantasy world find ourselves banging our heads on a virtual brick wall every time someone uses the term "myth" or "fairy tale" to mean something that is untrue. Myth is a way of looking at and understanding the world by means of story and symbol. That's why I like listening to Michael Meade's podcast, Living Myth, that looks at current events from a mythic perspective. This approach is every bit as valid and vital as the empirical approach, if not more so. In fact, the more I learn about the likes of quantum physics (not that I am anywhere near to understanding it!) the more I find that the two complement each other.

But what about things you're supposed to believe literally? If I say I'm a Christian (and I do) then it follows that I must believe in Jesus and the things that he's supposed to have done and said. There are those who say Jesus of Nazareth never existed as a historical figure. There are others who would come down on me like a ton of bricks (maybe from that proverbial wall) for daring to doubt a single semi-colon of the New Testament (even though the original Greek manuscripts don't have semi-colons).

How do I prise all this apart? Do I even try? When it comes to religious figures, can we ever tell history from myth? I don't pretend (or hope) to have a final answer on this, but here are some of my thoughts.

This Much Is True

It’s not up to us to say what is “realistic”. Often the most far-fetched episodes from our own lives or those of others turn out to be true.

I know this to be true from my own experience. I have had enough people - including professional therapists - disbelive or misunderstand the details of my unrequited, asexual love life. When writing Cage of Nightingales and its forthcoming sequels, I had to "tone it down" to make it believable. On the other hand, one of my brothers is a larger-than-life raconteur, who I know well enough to doubt half of what he tells me.

I know that once people doubted the jars in the story of the Water Into Wine could have been that big, until archeological remains were discovered. Likewise, I know there is still a fallacy in the United Kingdom that no Black people lived here until the arrival of the Empire Windrush in 1948. Just because you can't - or don't want to - believe something, that doesn't make it untrue. Think of all those climate deniers or flat earthers!

Then there's the matter of perception. We know from psychology that someone on the autistic spectrum or who is depressed or narcisistic is going to see the world in their own particular way. And that's true for everyone. If I tell you I see the world as alive with enchantment and symbolic meaning, you might struggle to see what I mean. I might see a miracle where you see coincidence or even just the everyday world. But does that make me wrong?

Mythical Thinking

- hero is a "great man" - the Titanic's size, splendour and name

- hubris (pride before the gods) - "even God couldn't sink this ship"

- harmatia (tragic flaw) - not enough lifeboats

- reversal of fortune - ship hits an iceberg

- pathos (suffering/calamity) - people drown]

Gods and Mortals

As archetypal qualities, spiritual essences are implicit rather than explicit in the material world. However, they are real... When, occasionally, an individual human being approaches one of these archetypes in her or his life, then in a real sense that person is an embodiment of that essence. This person is respected and viewed from then on as an image of perfection that is identical with the essence, and there is a confusion between the historical person and the otherworldly archetype. This is how a saint, or divine human being is recognized. Human limitations are transcended, and the historical person enters the realm of timelessness. Because the archetypes were seen as individual gods and goddesses, their qualities were conserved through the change from polytheism to monotheism.

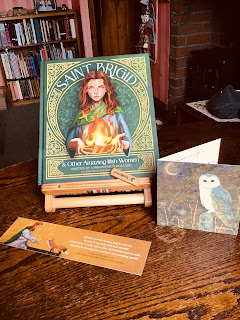

This is why I have little problem with, for example, the apparent conflation of St Brigid of Kildare with the Celtic triple goddess Brigid. People felt that she embodied the qualities of the goddess she was named for, and this association became stronger in the retelling.

This is why I have little patience with people telling me that Christian saints, festivals, or even beliefs about Jesus are "really" pagan, as if that somehow negates them. Who would gleefully point out the similarity of Jesus' story to that of Mithras or Lugh, as if that renders my faith invalid. To my way of thinking, the connection strengthens them.

If I truly believe that Jesus is "the loveliness of all lovely desires" then I have to believe that he fulfils the longings of all religions and beliefs. Just as much as the Gospel writers saw him as fulfilling the longings of the Jewish people. (And don't get me started on just how Jewish the New Testament is. Unless we turn to actual Jewish sources for understanding, Gentiles will never grasp it fully). Early Christians from the Greek world saw Jesus as fulfilling the wisdom of the philosophers, such as Socrates and Plato. There are some people now who see Jesus as fulfilling the Buddhist way, or as an avatar of Vishnu.

None of that means Jesus of Nazareth was not a real person. In light of the evidence, I find it very hard to believe that he was not. Whether or not he perfectly embodied the essence of the Divine is not something I can prove or disprove. I believe it. But I see the world as alive with meaning - I can't make you see through my eyes.

However, let's not fall into the trap of trying to look into the past and dictate what "could" or "could not" have happend. That way madness lies.

As that other kindred spirit Susanna Clarke wrote in Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell:

A hundred years ago the magio-historian Valentine Munday, denied that the Other Lands existed. He thought that the men who claimed to have been there were all liars... Of course... Munday went on to deny that America existed, and then France and so on. I believe that by the time he died he had long since given up Scotland and was beginning to entertain doubts of Carlisle...

Sources

Legends from Lindisfarne Preorder

Comments

Post a Comment