LGBT+ History Month: Carlo and the Castrati

|

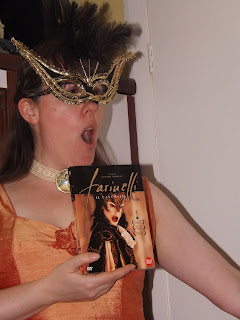

| Me and Carlo: BBFs (by Kirsty Rolfe) |

I’d like to introduce you to Carlo.

Some of you may have met him before, but he’s one of the two heroes of Cage of Nightingales, the first of my Angelio novels, which is finally due to be published this year by Deep Hearts YA. Carlo is a castrato singer. When we first meet him, he’s thirteen years old, a student at the Conservatorio Archangeli, a prestigious music school in the city-state of Angelio. He’s talented, kind, loves beautiful things, hates arguments, can be flirty, and just wants a friend who sees him as more than a beautiful voice.

And he’s canonically asexual and biromantic. Just thought I’d get that out there.

Carlo is named after Carlo Broschi (aka Farinelli), the most famous of the castrato singers of the 18th century. I’ve written quite a bit about Farinelli and the other castrati on this blog, but as it’s LGBT+ History Month (in the UK at least) I thought I’d share with you a few facts about them.

|

| “Portrait Group: The Singer Farinelli and Friends” (detail) by Jacopo Amigoni (1892-1752]. Oil on canvas. National Galley of Victoria, Melbourne, Australia. |

- It was pretty much an Italian thing. Other countries, such as China and the Ottoman Empire, had a tradition of creating eunuchs to supervise the female quarters of royal palaces, and for high administrative roles. (They couldn’t found a rival dynasty.) Italy was kind of unique from the C16th onwards in mass-producing eunuchs who were specifically castrated in order to preserve their soprano singing voices. Even though the singers and surgeons were not exclusively Italian, the sound of the castrato voice was very much associated with Italian music.

- It was illegal, but that didn’t stop people doing it. There were numerous penalties and laws at various times against castration, saying it must only be done for medical reasons, or that the boy must consent, but it actually took place all over Italy, albeit in a clandestine way. The travelling musicologist Dr Charles Burney (father of Evelina author Frances Burney) claimed no one in Italy could tell him precisely where it was done. “In Milan they told me Venice. In Venice they referred me to Bologna, in Bologna they denied the fact and blamed Florence. Florence attributed it to Rome and Rome to Naples.” (1) Many boys were told by their parents that they had been castrated for medical reasons, although remarks by some adult castrati shows they doubted these explanations.

- Some boys actually asked for castration. It may seem incredible to modern readers, but a castrato singing voice was a route to fame and fortune. If a boy from a poor background was discovered by his local choirmaster to have a beautiful soprano voice, he might be tempted to keep it. Luigi Marchesi, for example, demanded castration on the advice of his music teacher, against his parents’ wishes. He became one of the greatest castrati of the late 18th century.

- Castrati were the superstars of their day. In the Italian opera of the early 18th century, castrati were the leading men of the show, taking the parts of gods and heroes. The top singers were extremely well-paid (unlike the composers!) and were fêted in the homes of aristocracy and royalty. Some of them acted like real divas, too! It’s impossible for us now to know what the leading castrati really sounded like, or what made their voices so fashionable. There are early C20th recordings of the “last castrato” Alessandro Moreschi, but they can’t really compare with hearing someone like Farinelli, live, at the height of his powers. Farinelli was said to have a vocal range of 4 octaves - between C2 and C5 - “so perfect, so powerful, so sonorous and it’s range so rich in both the high and low registers, that it’s equal has never been heard in our time.” (2)

- The gamble didn’t always pay off. Castration didn’t necessarily result in the preservation of a flawless singing voice. In which case, a person would be left with the speaking voice and body of a eunuch, but none of the social acclaim.

- They saw themselves as a third gender. The process of castration meant a halt to the production of testosterone that brings on puberty, and sometimes an increase in feminine hormones. This gave castrati an androgynous appearance, often described as angelic - softer bodies, beardless faces and high voices. Many of them liked to be called putti (boys) regardless of their age. Moreover, many of them performed as women on stage (particularly in the Papal States, where women were forbidden from treading the boards). And some wore feminine accessories such as veils and corsets in real life. Filippo Balatri (the castrato poet) wrote of himself:

"I was already made into a mixed gender,

That is a soprano, and was quite young.

I apply myself to singing in the most human style

Doing so with industry and a good vocation."

"He asked me first if I am

Man or woman, where I came from,

If people like me are born

with this voice and skill, or rain down

from the sky. In confusion I reply:

If I say "man", I lie

"Woman" I certainly shall not say

and "neuter" would make me blush". (3)

- Many women found them attractive. I can completely relate to the aesthetic attraction of an androgynous man. Fans of the castrati were known to faint at performances. For many aristocratic women, the love of a castrato was an idealised one, driven by his pure voice and angelic appearance. For others, the attraction lay in the fact that their lover was incapable of getting them pregnant. For yet others, it may have been an expression of their own queerness (although they wouldn’t have used our modern terminology). Several castrati had love affairs, and long-term relationships with women. Needless to say, men found them attractive too, although this could occasionally backfire. Casanova famously had an assignation with a castrato called Bellino, who turned out to be a woman in disguise!

- They were forbidden to marry. The struggle for marriage equality is nothing new. Pope Sixtus V ruled in 1587 that the “frigid and impotent” could not marry, in the grounds that they could not reproduce. As virtually all the castrati were practising Catholics, this was a big problem. One singer (Cortona) petitioned Pope Innocent XI for permission to marry, saying his castration had been incomplete.The Pope replied, “Let him be castrated better!” Others got around the ban by marrying Protestant women. The ban was only officially reversed in 1977.

- They were subject to homophobia/transphobia/aphobia. Castrati were “subject to taunts, verbal abuse, coercion, physical brutalisation, and psychological intimidation”. (4) They were called capons, non integri (not whole), unnatural, cowards, cripples, weak-minded; and their bodies likened to elephants, apes and spiders. They were often assumed to be the passive partner in a male/male relationship, regardless of their actual sexuality. Even the very successful were not immune to being satirised.

- They are asexual icons. (To me). Patrick Barber says, “the castrato embodied the trinity - man, woman and child - from an asexual personality”. (5) Obviously, not all castrati were literally asexual in orientation. Some were; some weren’t. (Going by the available evidence). But they give me asexual vibes. Their androgyny, lack of sexual threat, and angelic voices makes them very attractive to me. As a heteroromantic, asexual woman, I would definitely be among their swooning fans.

As we consider our LGBT+ history this month, let us not forget the castrati. Although they lived in a different age, which saw gender and sexuality in a different way, many of their experiences and struggles were similar to ours, and even paved the way for us today.

|

| Me imitating Farinelli |

- The Present State of Music in France and Italy, 1771, quoted in Barber, Patrick, The World of the Castrati. Trans. Margaret Crosland. London: 1996.

- Barber, p. 93

- Frutti del mondo Naples: 1924

- Finucci, Valeria, The Manly Masquerade. Durham and London: 2003. p. 239

- Barber p. 17

Comments

Post a Comment